What do Bruno Mars’ funky beats, Beyoncé in traditional Indian attire with henna tattoos, Katy Perry dressed up as a geisha, and Miley Cyrus in a rainbow-colored bindi have in common? Each one has gotten into some hot water over cultural appropriation.

As more than a buzzword used to criticize music videos or insensitive TV commercials, the debate over cultural appropriation asks this question: When does cultural borrowing turn into exploitation?

Unsure exactly what cultural appropriation means or when intercultural “influence” goes from respectful to insulting or even harmful? To answer this question, we surveyed 958 people about how well they understood the concept. We further asked them where they drew the line and how cultural appropriation impacted political movements and policy issues like Black Lives Matter and Dreamers. Read on as we explore their opinions and more.

A Movement Or A Menace?

Cultural appropriation, sometimes referred to as cultural misappropriation, is a social concept with multiple definitions and interpretations. For this study, we utilized a popular definition from a reputable source for consistency.

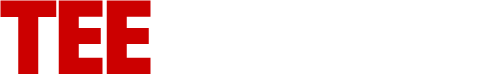

According to HuffPost, cultural appropriation is defined as being “broadly applied to borrowing that is in some way inappropriate, unauthorised or undesirable.” Similar to the time Kim Kardashian dressed up as the late singer Aaliyah (who was black), this “borrowing” may seem harmless or unintentional to some. To others, however, it can constitute disrespect and even racism. In contrast, some argue cultural appropriation doesn’t exist in popular culture – or doesn’t matter.

So how do most people define cultural appropriation and how important it is today? Over 1 in 3 people agreed cultural appropriation involved adopting traits of another culture in a disrespectful or misunderstood way. However, just as many people described the term as adopting the traits of another culture. Their descriptions didn’t mention whether this was done in a harmful or dangerous way.

Nearly 1 in 4 people provided a response not related to the concept. And another 3 percent described cultural appreciation instead.

When asked whether cultural appropriation exists, older people were more likely to agree than younger generations. While 89 percent of baby boomers and 87 percent of Gen Xers believed cultural appropriation existed, 85 percent of millennials and 81 percent of Gen Zers said the same.

A Community Perspective

Above you can see the diversity of responses we received when people were asked to describe cultural appropriation.

One multiracial man described it as a cultural exchange in “victim mode,” while a Caucasian man said cultural appropriation was the “fictionalized belief that certain cultures have ownership over some things.”

Still, some people recognized the harmful effects of cultural appropriation. One multiracial woman described the concept as “mimicking behaviors of a culture without knowing the full meaning of the behavior.” A Caucasian woman echoed this sentiment by saying cultural appropriation was “using the trappings of a culture other than your own without really understanding/honoring that culture.” While responses varied significantly, one thing was sure – most people didn’t fully agree on cultural appropriation or how harmful it can be.

Abusive Actions

While respondents might not have agreed on the definition or impact of cultural appropriation, we asked them to rank the harmfulness of certain cultural actions.

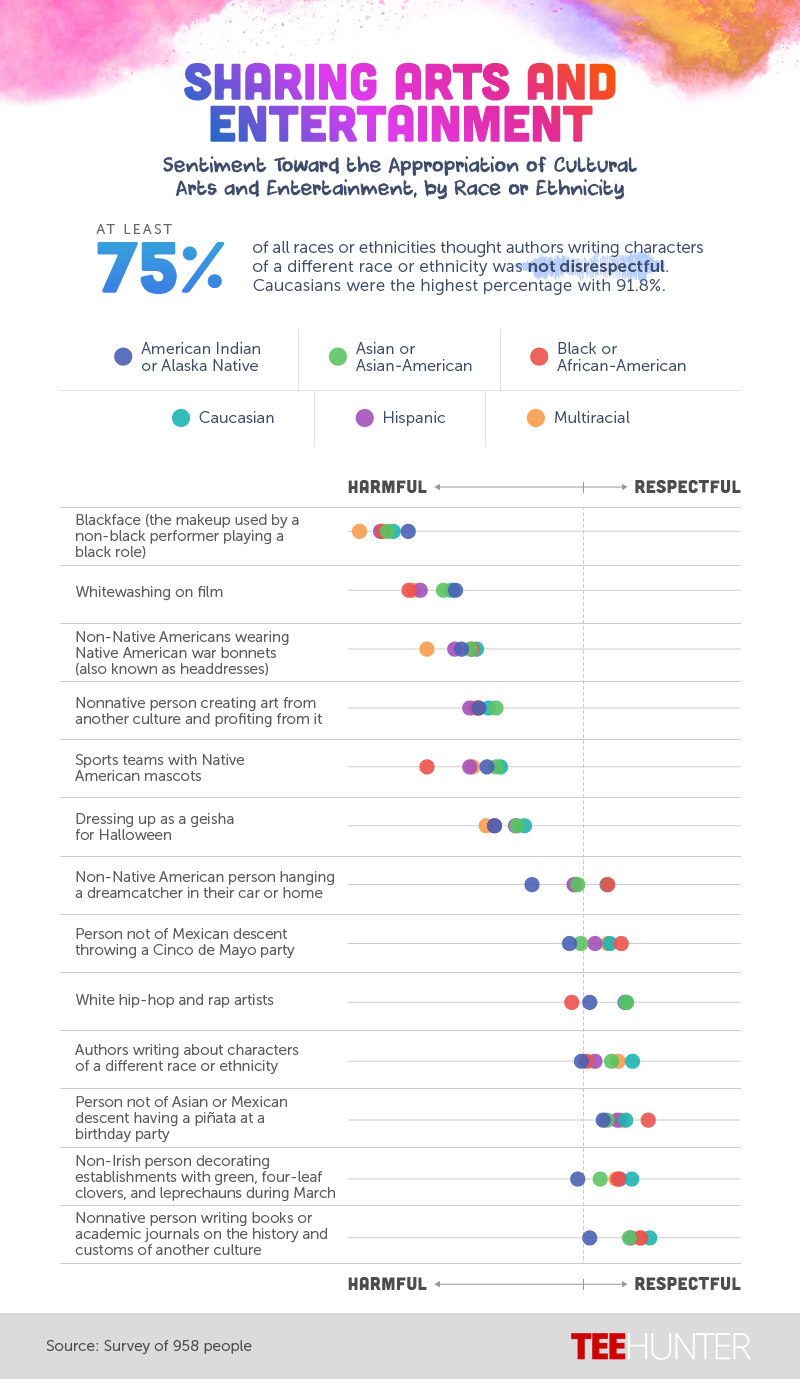

Seventy-eight percent of people identified blackface as the most harmful action associated with cultural appropriation. As a process of wearing dark makeup to appear black for comedic performances, blackface dates as far back as the early 19th century. Beyond physical appearance, blackface involves stereotypical behavior for racial parody. Used today as a part of Halloween costumes or in pop culture performances, those using blackface often claim there’s no malice or hatred attached to their actions.

Another 70 percent of people said whitewashing on film was harmful, in addition to claiming a culinary dish created by another culture. Disney was recently accused of whitewashing on the set of the live-action version of “Aladdin,” where background characters had their skin darkened to make the main character’s skin seem lighter.

Roughly half of people said sports teams with Native American mascots were also harmful. In response to a growing wave of criticism, the Cleveland Indians announced they would replace their mascot, Chief Wahoo, from uniforms by 2019. Despite similar pressure, the Washington Redskins have yet to make a similar effort.

Mainstream Appropriation

Blackface has over 100 years of history in the U.S., but that doesn’t mean it can’t still happen in present time despite the stigma surrounding it. In 2017, Kim Kardashian released photographs for her newly launched KKW beauty brand. Critics were quick to point out that Kim’s skin was noticeably darker in the images, accusing the reality-TV star of modern-day blackface. While Kim denied the accusations, this isn’t the first time the Kardashians have been under fire for cultural appropriation.

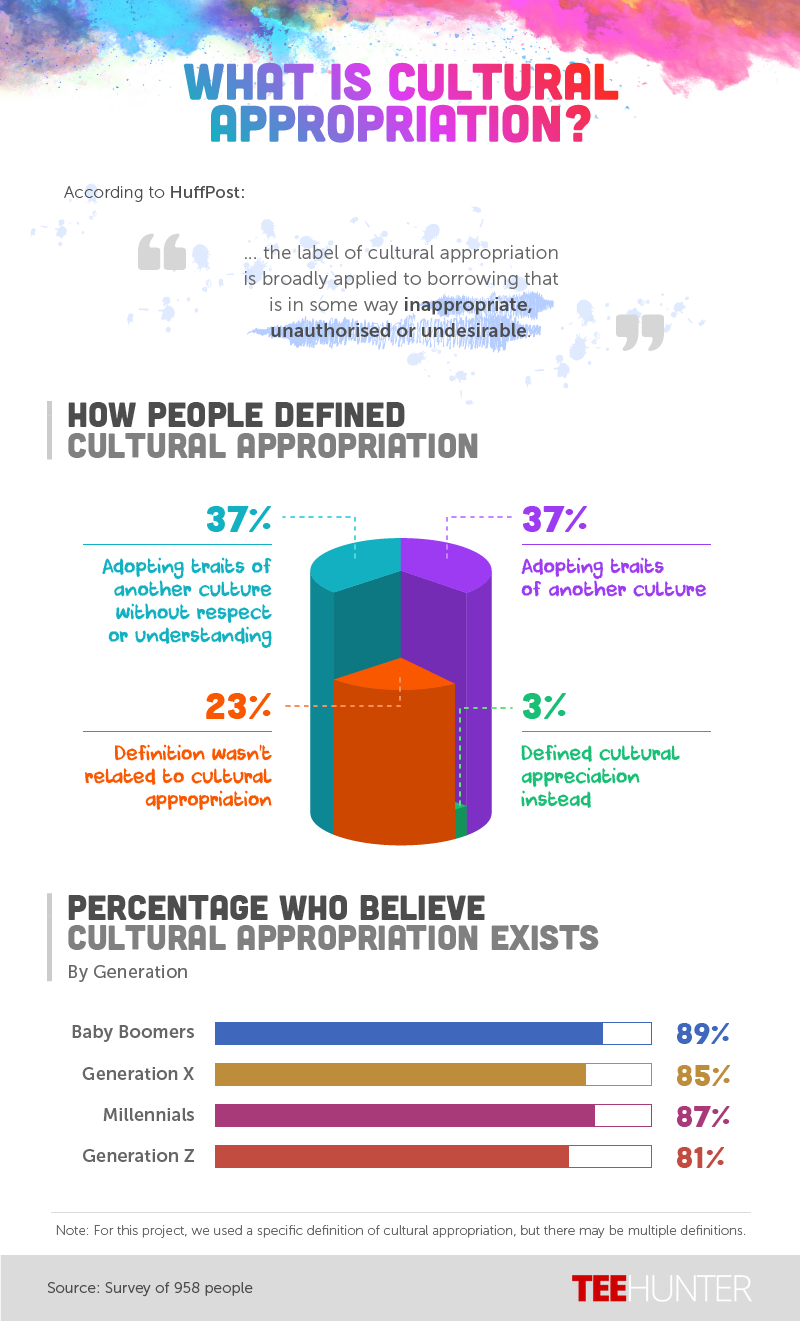

Regardless of the intention, it’s important to recognize how offensive many people consider blackface. While a majority of people considered this action to be harmful (including 83 percent of Hispanics and 82 percent of American Indians or Alaska Natives), 75 percent of black or African-American respondents agreed the use of blackface was disrespectful.

The Washington Redskins get a lot of heat for their culturally insensitive team name and logo, but they aren’t the only professional sports team to experience these accusations. The Cleveland Indians, Chicago Blackhawks, Atlanta Braves, and Florida State Seminoles utilize Native American imagery as a part of their branding, although some may do it less offensive than others. According to 67 percent of black and African-American respondents, 59 percent of multiracial people, and 57 percent of Hispanics, the use of a Native American mascot was considered disrespectful regardless of the intent. Only 56 percent of American Indians or Alaska Natives said the same.

Good Cultural Vibes?

Music festivals like Coachella have a sordid history with cultural appropriation, particularly in the way people dress.

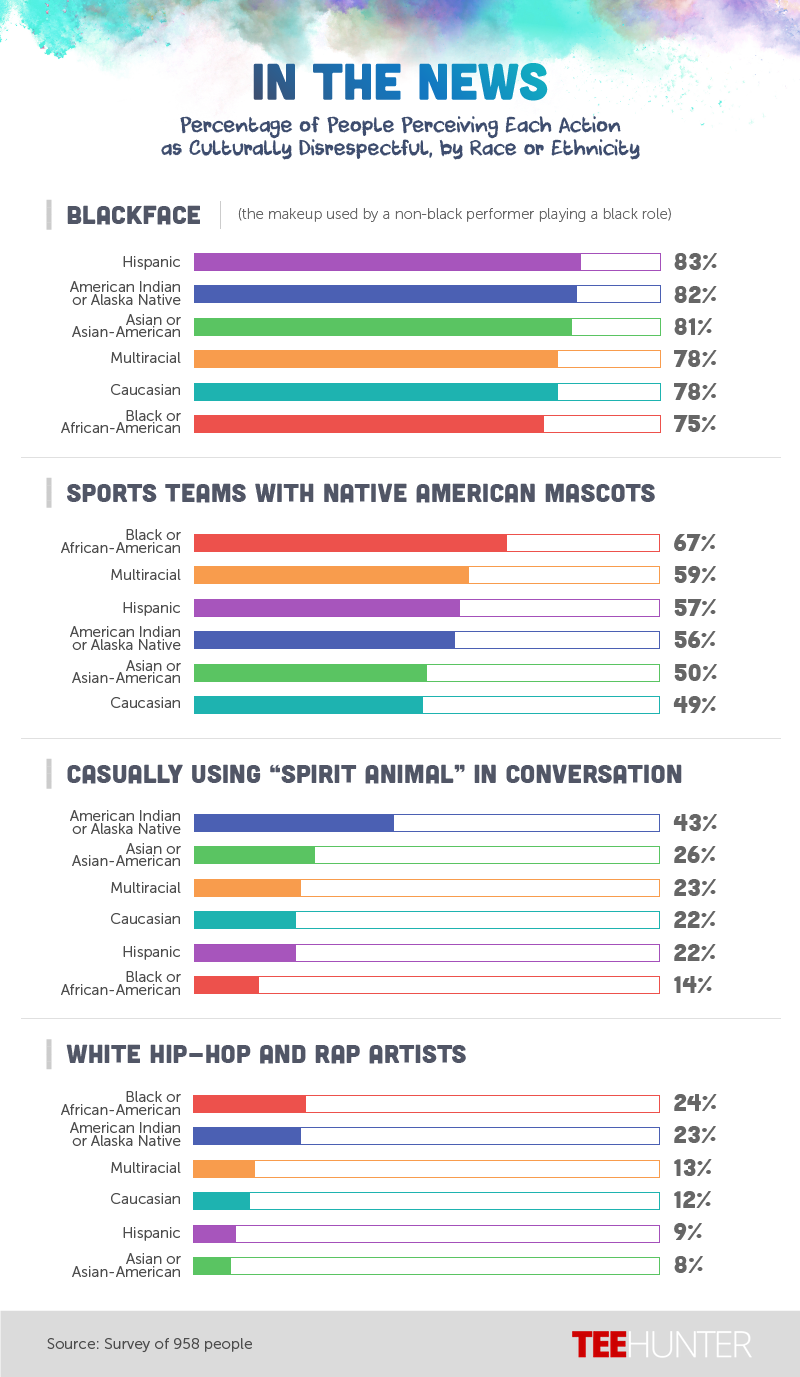

Wearing traditional Native American war bonnets (or headdresses) is among the most visible forms of appropriation and is typically seen as the most harmful. While 73 percent of multiracial Americans and 63 percent of black and Hispanic respondents agreed non-Native Americans wearing headdresses to music festivals was offensive, slightly fewer (62 percent) of American Indians or Alaska Natives said the same. Either way, some festivals have gone so far as to ban Native American war bonnets at their shows.

Another form of cultural appropriation at music festivals is jeweled dots on the forehead to look like Hindu bindi. In Hindu culture, the red bindi is associated with blood sacrifices to appease the gods. While modern Hindu women (and occasionally men) wear a bindi as a beauty accessory or fashion, it’s important to recognize its cultural significance. Sixty-one percent of American Indians or Alaska Natives found wearing these jeweled dots to music festivals offensive compared to 50 percent of multiracial respondents and 42 percent of Caucasian participants.

Over a third of multiracial (38 percent) and black or African-American respondents (28 percent) also said non-African-Americans wearing dreadlocks or cornrows at music festivals was offensive. As a more recently controversial form of cultural appropriation, some critics argue the use of these hairstyles by nonnatives has achieved mainstream acceptance, while black people are sometimes seen as unprofessional or inappropriate for wearing the same.

Cultured Cuisine

What makes certain cuisines authentic varies according to people polled. While some say a cultural food item is authentic as long as its roots are based on the country of origin or its history, others suggest it requires someone from that culture to prepare it as well.

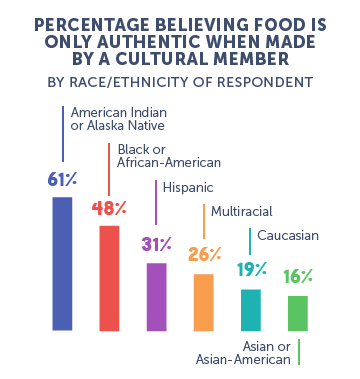

Sixty-one percent of American Indians or Alaska Natives believed food was only authentic when a member of its cultural community prepared it. Forty-eight percent of black or African-American participants said the same, followed by 31 perfect of Hispanics. Before you start to wonder if that calls into question all of your favorite foods, only 19 percent of Caucasians and 16 percent of Asians or Asian-Americans said the same.

If you enjoy a particular cuisine from a culture that’s not your own, you might wonder how cultural appropriation impacts your dining experience.

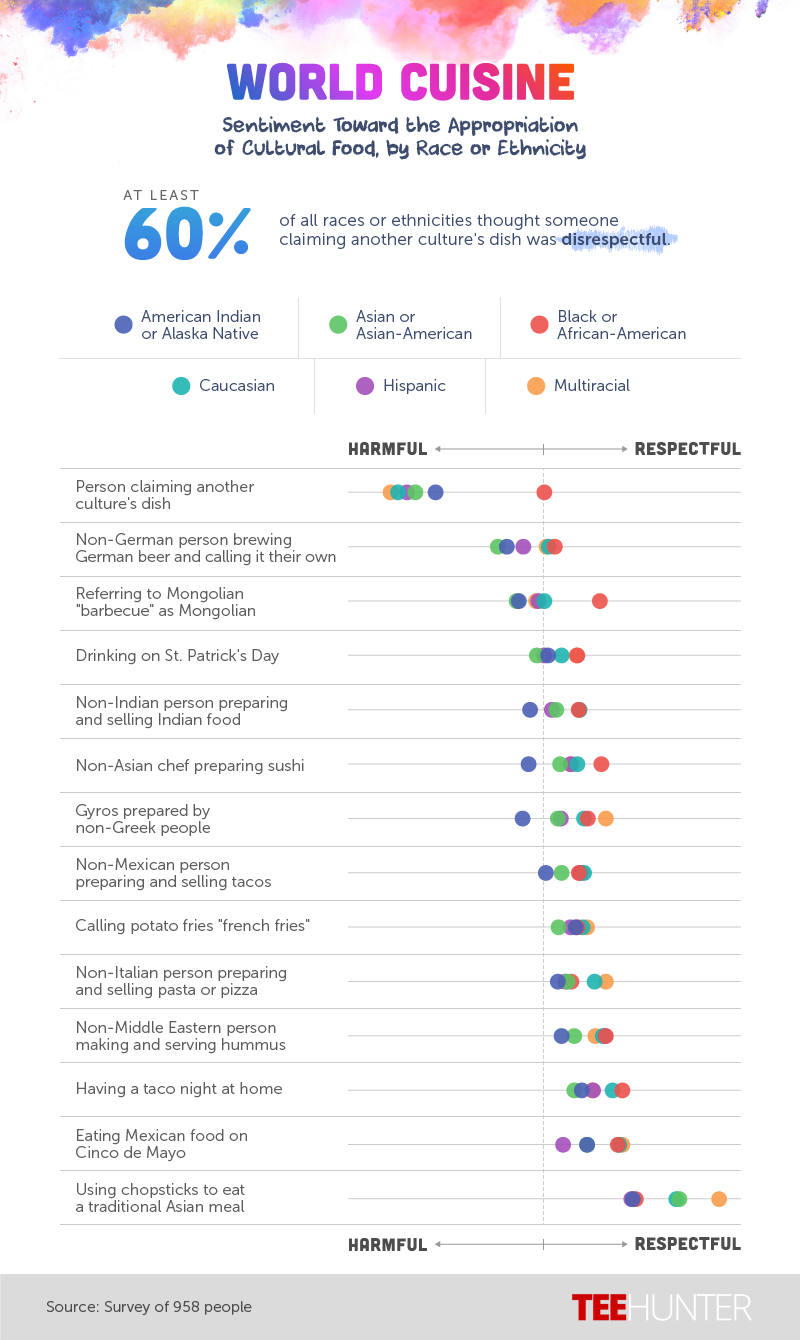

Claiming a dish from another culture was seen as almost universally harmful by people polled regardless of their race or ethnicity. Multiracial respondents ranked it as the most harmful, while black or African-American people were the least likely to rank it offensive. Hispanic people, Asian or Asian-Americans, and American Indians or Alaska Natives had a similar perspective on non-German people brewing German beer and calling it their own.

In contrast, many food-related activities were seen as showing respect to their native cultures. Like non-Mexicans preparing and selling tacos or non-Middle Eastern people making and serving hummus, as long as the cultural significance of the meal remained intact, it was all good. Even eating these foods and serving them in your home was seen as a sign of respect.

The least harmful thing you can do according to people polled? Use chopsticks to eat a traditional Asian meal. And there are simple steps you can follow if you aren’t entirely sure how to use them.

Degrees of Distastefulness

Unlike food, people were more likely to see certain actions as harmful to other cultures.

Leading the way was blackface. Seen as harmful by most races or ethnicities on average, multiracial people ranked it as the most offensive. Multiracial people also saw whitewashing as the most harmful in addition to non-Native Americans wearing Native American headdresses and dressing up as a geisha for Halloween. The multiracial population in America continues to grow, and many face unique experiences as a result of their racial identity. These experiences sometimes include racial and discriminatory microaggressions, defined as unconscious acts or statements that can insult or discriminate.

Sports teams with Native American mascots were also ranked among the most harmful actions, although black or African-Americans, Hispanics, and multiracial respondents ranked these mascots as more harmful than Native Americans or Alaska Natives surveyed.

Nonnatives experiencing cultural events, including throwing a Cinco de Mayo party or decorating for St. Patrick’s Day, was seen as more respectful.

A War of Words

The way people interact with a different culture can sometimes cross a respectable line, even without negative intentions.

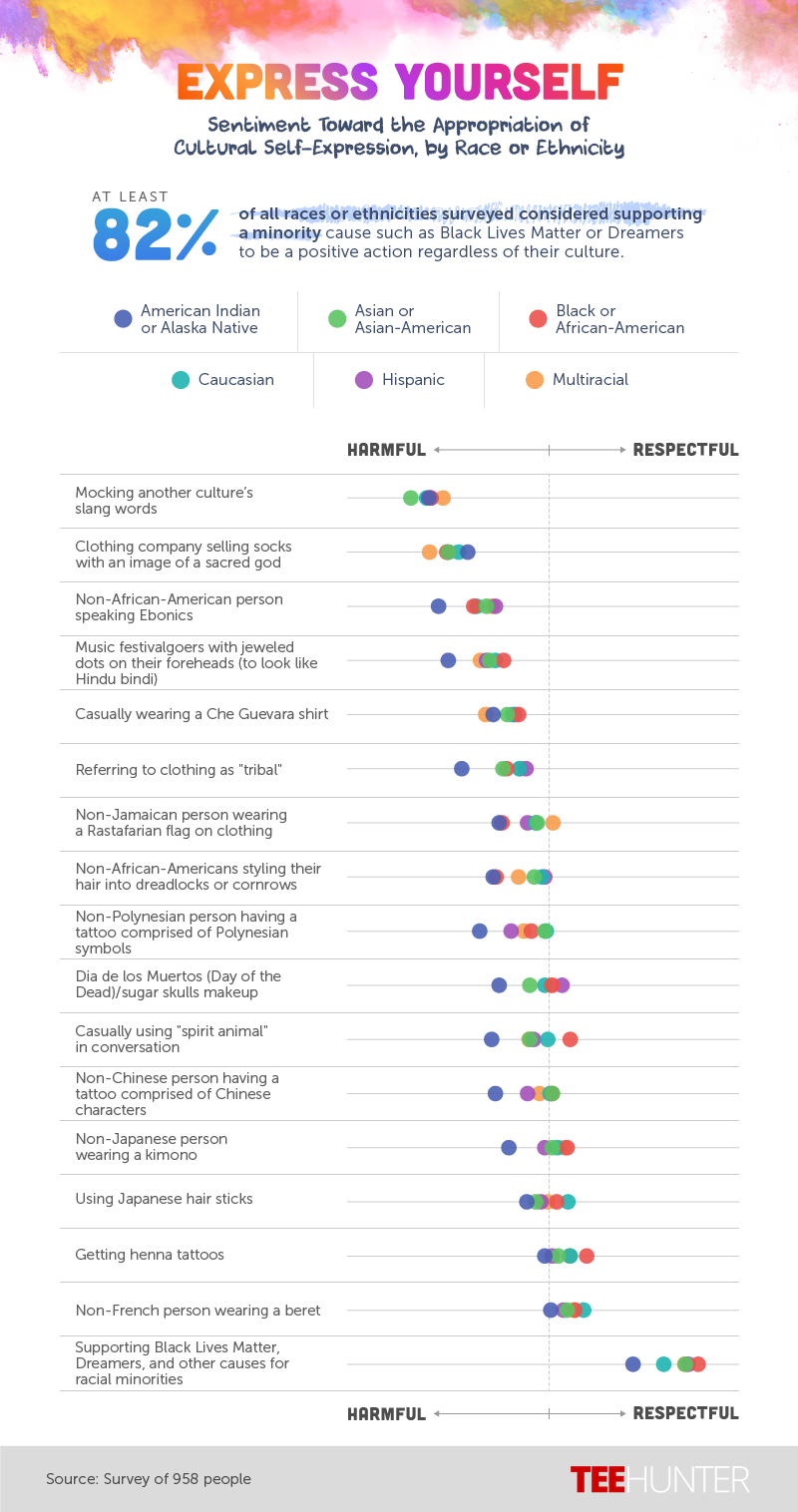

When asked about cultural self-expression, people ranked linguistic appropriation among the most harmful actions on average. Using another culture’s language out of content or incorrectly can be seen as deeply offensive, and mocking another culture’s slang words was the worst of them all. Even terms like “bae” and “fleek” have backgrounds in black culture, and while that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use them in casual conversation, you might at least want to know where they come from.

Other actions seen as disrespectful or harmful to the cultures in question included clothing companies selling t-shirts with images of a sacred god, non-African-Americans speaking in Ebonics, and people attending music festivals dressed in bindi. Certain music festivals have a history of offensive attire. And while attendees may not realize why their clothing choice is offense (or even what culture it represents), some festivals have banned attendees from wearing Native American headdresses (or war bonnets) to avoid offense.

According to our survey, all races and ethnicities ranked supporting a minority-related cause or policy – including Black Likes Matter and Dreamers – as a positive action regardless of culture.

Trying New Things

From what you eat to the way you talk and wear, there’s sometimes a very clear difference between respectful influence and potentially harmful cultural appropriation.

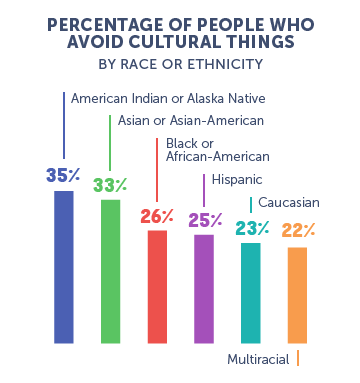

Still, that doesn’t keep some people from completely avoiding cultural activities. Only 35 percent of American Indians or Alaska Natives, followed by 33 percent of Asian or Asian-Americans, 26 percent of black or African-Americans, and 25 percent of Hispanic respondents said they refrained from any activities associated with a culture not their own. Caucasian (23 percent) and multiracial people (22 percent) were the least likely to let the fear of cultural appropriate stop them.

Drawing the Line

People surveyed didn’t entirely agree on how to define cultural appropriation or if the concept even existed, but many agreed on the actions that were seen as disrespectful and potentially harmful to other cultures. Things like blackface, linguistic appropriations, and even whitewashing were ranked as harmful by those polled. Even more modern controversial debates (including sports teams with Native American mascots) were more likely to be ranked as harmful than not.

Methodology

We collected survey responses from 958 people via survey. Fifty-three percent of participants were men and 47 percent were women. Five percent of participants were American Indian or Alaska Native, 8 percent were Asian or Asian-American, 6 percent were black or African-American, 71 percent were Caucasian, 6 percent were Hispanic, and 4 percent were multiracial. Eleven percent of participants were baby boomers, 15 percent were Gen Xers, 67 percent were millennials, and 7 percent were Gen Zers.

Participants ranged in age from 18 to 74, with a mean of 35.6 and a standard deviation of 11.9. Demographic groups with less than 20 participants were excluded from individual analysis. We weighted the data to the 2016 U.S. Census for gender, age and race.

The data we are presenting rely on self-reporting. There are many issues with self-reported data. These issues include but are not limited to: selective memory, telescoping, attribution, and exaggeration.

No statistical testing was performed, so the claims listed above are based on means alone. As such, this content is purely exploratory, and future research should approach this topic more rigorously.

Sources

- https://www.teenvogue.com/gallery/celebrities-cultural-appropriation-miley-cyrus-katy-perry

- https://www.huffingtonpost.com/the-conversation-africa/cultural-appropriation-wh_b_10585184.html

- http://www.thisisinsider.com/kim-kardashian-aaliyah-halloween-costume-apology-2017-11

- https://noisey.vice.com/en_uk/article/rm8gb6/does-cultural-appropriation-in-pop-music-even-matter-oneofthoseface

- https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/blackface-birth-american-stereotype

- https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/01/aladdin-remake-disney-whitewashing

- https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/redskins-pressured-to-change-logo-follow-indians-axing-of-chief-wahoo

- https://www.thespruce.com/what-makes-mexican-food-authentic-2342843

- http://thewoksoflife.com/how-to/how-to-use-chopsticks/

- http://societyforpsychotherapy.org/understanding-the-stressors-and-types-of-discrimination-that-can-affect-multiracial-individuals-things-to-address-and-avoid-in-psychotherapy-practice/

- http://metro.co.uk/2017/08/11/we-need-to-talk-about-the-cultural-appropriation-of-sign-language-6845467/

- https://www.refinery29.com/2018/02/142047/black-slang-words-meanings-history

- https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/9bgxd3/we-spoke-to-some-people-with-culturally-offensive-outfits-at-coachella

- https://www.wmagazine.com/story/kim-kardashian-kkw-beauty-campaign-controversy-keeping-up-with-the-kardashians

- https://www.marieclaire.com/celebrity/news/a27683/kardashian-enterprises-cultural-appropriation/

- http://www.statepress.com/article/2016/04/when-traditional-sports-teams-mascots-are-offensive

- http://www.eonline.com/fr/news/563845/music-festival-is-banning-cultural-appropriation-aka-hipsters-wearing-native-american-headdresses

- http://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/bindi-investigating-true-meaning-behind-hindu-forehead-dot-007272

- https://fashionista.com/2018/01/black-hair-braids-cultural-appropriation-media-erasure

Fair Use Statement

Think you learned something new about cultural appropriation from our study? Feel free to share these results with your readers for any noncommercial use. Just ensure a link back to this page so that our contributors earn credit for their work too.